Review by Martin K.A. Morgan

At sunrise on Wednesday, August 10, 1864, the Confederate garrison inside Fort Morgan, Alabama awoke to find federal sharpshooters positioned throughout the sand dunes immediately around the structure. Marking the beginning of a two-week long siege, the sharpshooters fixed their rifle-sights on the fort and fired at anything that moved. They produced a “rain of balls” so relentless and effective that one Confederate soldier commented, “…no one can show his head above the parapet” because of the bullets “whizzing all over the fort.” The garrison considered the sharpshooters “very daring” because they crept so close to the fort – some as close as 250 yards from its masonry walls. Being prevented from firing by such accurate rifle fire, Fort Morgan’s artillery could do nothing to interfere with the landing of hundreds of fresh Union troops later that day. After sunset, 200 Union soldiers began digging trenches, filling sandbags, shaping artillery revetments and generally advancing a federal siege line that gradually tightened the noose around the old fort.

This process continued throughout the middle of August and permitted the emplacement of heavy guns and siege mortars that ultimately subjected Fort Morgan to a heavy bombardment that resulted in the garrison’s capitulation. Although the most awesome weapons available to the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army caused the fall of Fort Morgan, Union sharpshooters did too. They suppressed the offensive firepower of a well-armed Confederate garrison and made it possible to bring up the big guns that battered the fort into submission. They accomplished this task with a weapon that fought in every Civil War clash of arms – a weapon often credited with being the most murderous instrument of warfare on the battlefield: the rifle musket.

This particular class of musket emerged during the 1830s and 1840s from a series of technological advances in shoulder fired arms and ammunition that made it possible for an individual shooter to direct accurate rifle fire against targets at greater ranges and with unprecedented accuracy. For over fifty years now, historians have deterministically interpreted the rifle musket as being the technology responsible for the extreme bloodletting so closely associated with Civil War battles.

[read more=”Click here to Read More” less=”Read Less”]

In “Civil War Infantry Assault Tactics” (Military Affairs, Summer 1961), John K. Mahon concluded that the rifle musket “caused battles to be at once much longer in time and less decisive in outcome.” He also labeled the linear, Napoleonic assault formations used throughout the conflict as obsolete when confronted with the overwhelming and accurate firepower of the rifle muskets that opposed them. Grady Mc Whiney and Perry Jamieson further developed this deterministic interpretation with their 1982 book Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage. To them, the weapon’s deadly accuracy caused horrendous losses during the war’s early maneuver battles and ultimately the corresponding trend toward trenches, field fortifications and static warfare after 1864. Often referred to as the “rifle revolution” among scholars, this orthodoxy has dominated the way historians have understood the role of the weapon in the conflict. But did the rifle musket dramatically change combat during the war?

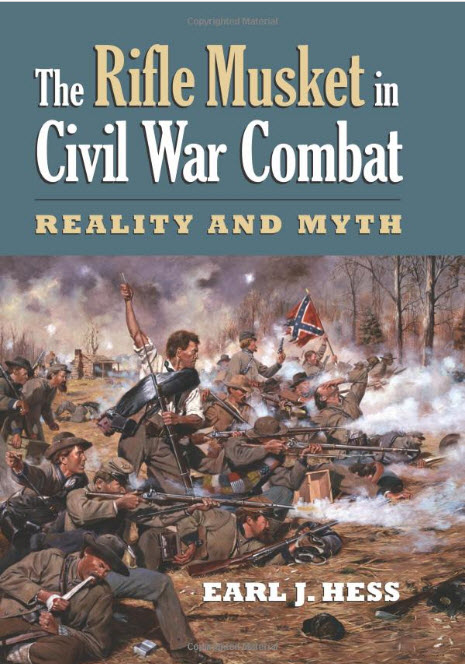

That question is answered with a direct challenge to the “rifle revolution” orthodoxy in The Rifle Musket in Civil War Combat: Reality and Myth by Earl J. Hess. In the book, the author argues that the impact of the weapon has been “exaggerated, misunderstood, and understudied ever since Union and Confederate volunteers shouldered firearms” (p. 197). The central argument of the book asserts that the rifle musket exerted “only an incremental, limited effect on Civil War combat” (p. 4) and that it therefore did not decisively alter the course of the war as the previous scholarship suggests. The Rifle Musket in Civil War Combat analyzes a series of major infantry engagements from the Western theater of the war and concludes that riflemen in linear formations typically delivered fire against their opponents at less 100 yards range.

Significantly closer than previously thought, this range barely took advantage of the rifle musket’s capability and was well within the effective range of smoothbore weapons in massed, volley fire formations. Hess compares these Civil War battles against sixteen major European clashes to prove that the smoothbore musket actually produced greater bloodshed there than the rifle did during the American Civil War. While his most dramatic insights are reserved for the rifle’s role in linear tactics, Hess admits that the weapon did indeed have an impact on skirmishing and sniping albeit a marginal one. When it is considered that sharpshooters using the rifle musket materially altered the investment/siege operations at places like Fort Morgan, it seems that the weapon may have influenced sniping more than Hess is willing to admit.

That trivial criticism aside, this provocative book offers a much needed new interpretation of a firmly entrenched and persistent myth regarding Civil War combat and should therefore be enthusiastically received by Civil War scholars.[/read]