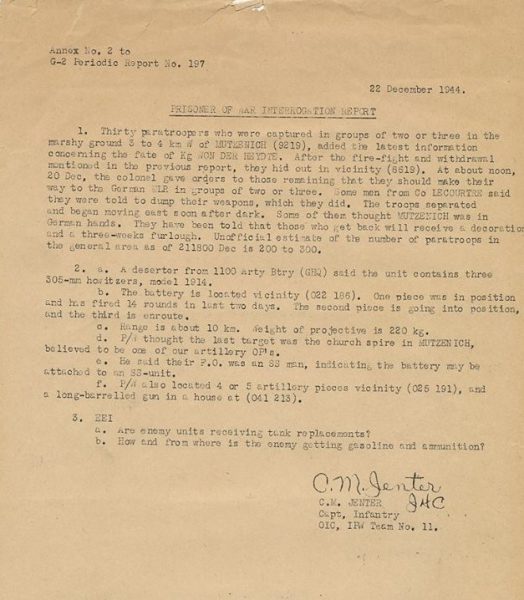

In picturesque Monschau– famous for its slate-roofed half-timbered houses– exhausted Fallschirmjäger desiring to surrender to U.S. forces sought out towns people. Better to give up to fellow Germans than risk being shot when surrendering to the enemy. This gained new import with rumors from the Latrinenparole that SS men– Kampgruppe Peiper– had murdered surrendering Americans just south of where they had landed. Between 21 and 24 December, over a hundred Fallschirmjäger gave themselves up to civilians in the town. “Sometimes we went out to take the paratroopers into custody,” remembered Paul Henze with its military government, “but usually we told the tactical troops of the MPs where the paratroopers were located and they went to pick them up. Nearly all were suffering from exposure and trench foot.”

by Danny S Parker author of FATAL CROSSROADS & HITLERS WARRIOR www.dannysparker.com

Also read Operation Stösser: Kampfgruppe Von der Heydte in the Ardennes (Part I)

The American military government officials knew nothing of the extent of the parachute operation– many estimating it to contain several thousand men that might suddenly rise up confront the unwary. The military government had made its headquarters in the Hotel Horchem– the finest of the twelve hotels in the town, disproportionately endowed as Monschau was a famous destination for honeymooners. Captain Robert A. Goetscheus, the head of the military government and a lawyer from Indianapolis, could not be too sure that his otherwise complacent citizens might suddenly revert to their previous sympathies.

The relationship of the 2,600 natives of Monschau to the early occupation had been uneasy since the Americans had taken over in September. Food, medical supplies and clothing had been short all autumn and many citizens were bored, unable to freely come and go and limited by curfews. Several locals made the observation that the Nazi government had never been this oppressive. However, the worst had come in October when, the members of Combat Command B of the 5th Armored Division– whose commander was wildly anti-German– had suddenly forcibly evacuated all the residents of nearby Kalterherberg and proceeded to loot the town. Even in Monschau there was a huge problem with thievery, GIs making off with furniture, radios, stoves and even cars. Then too, the non-fraternization policy was a total failure and by November, every willing German woman in Monschau had been seduced.

For weeks, the U.S. V Corps worried that sympathizers in the town were feeding information to the Germans, but the local government did not dwell of that certainty– as it was, enemy forces– known to include the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division– were on the sharp ridge line that looked right down into the town’s narrow cobble-stone streets. They could see everything and sometimes would even send artillery cascading into the town. Indeed a 15-man German patrol came into the town on 1 October and threatened the Burgomeister at pistol point at his own home for cooperating with the Americans.

The danger of living with the enemy so close became clear to the American occupational forces on Saturday, 16 December. That morning Monschau and the towns on either side, became the northernmost objective for Dietrich’s 6. Panzer Armee assault charged to the LXVII Armeekorps. In the German plan, the Vorausabteilung– the single partly-motorized detachment of the 326. Volksgrenadier Division built around 4 assault guns and the fusilier company was to strike through Monschau and push along the Eupen road to possibly help link up with Kampfgruppe von der Heydte. The northern talon of the German assault would unhinge the American forces defending in the Elsenborn area. Hitler himself had personally called for a super-heavy Jagdtiger Battalion (s. Panzerjäger Abteilung 653) to be participate in the advance on Eüpen, but delayed by the air power-pulverized German rail system to the rear, the single available company of 80 ton monsters had not arrived on the eve of the offensive. Still, very heavy artillery support was assigned: 405.Volksartillerie Korps and the 17. Volkswerfer Brigade turned tubes to the west for a massive barrage to help blast the infantry companies forward.

However, word had it that Genfldm. Model, himself had expressly forbidden artillery fire on Monschau, the fairy-tale resort and a favorite destination for honeymooners. Thus, the town largely escaped the pounding barrage that hit both the sectors to the north and south at 5:30 AM. One of the few shells to fall into Monschau a dawn struck right outside the Hotel Horchem spraying the dining room of the U.S. headquarters with shrapnel and sending everyone leaping under tables.

Thirty minutes later, a surprise attempt by the 326. Volksgrenadier Division to rush into Monschau along the winding Rohren road– materialized when the German infantry attempted to cross the road block on Rosenthalstrasse. Alerted by the shelling, troopers of F Company, 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron fired lethal canister from M5 Stuart light tanks at close range. The brazen German infantry pulled back with heavy losses. A second attempt, to enter the town at 8:30 AM from the “snake road” leading from Imgenbroich to the north and nearby wooded draws was also punished by American artillery, with the columns retreating in disarray. Meantime, unsophisticated human-wave assaults south of the town against the 3rd Battalion of the 99th Infantry in Höfen were similarly destroyed. These offensive jabs were so costly to Genmaj. Erwin Kaschner’s grenadiers– 20% casualties– that the division would make no further real contribution to Wacht Am Rhein. The Volksgrenadier mission to link up with Kampfgruppe von der Heydte never got started.

Back in the German village of Monschau, everyone was shaken. Over the succeeding nights, “artificial moonlight” eerily lit up the Monschau skyline. The illumination came from lines of searchlights on the German side, intended to help nighttime infantry assaults move forward. Enemy artillery barrages fell to the north and south upon nearby Mützenich hill and Höfen. Meanwhile, scores of German aircraft passed directly overhead on the night of December 17th while strong infantry assaults eddied back and forth against Höfen and Mützenich. The German assault followed on each of the following two days. These incursions were only turned back by the U.S. forces with great difficulty and the mood in town was somber.

With electricity out, on the night of 18 December, Capt. Goetcheus and his staff, has supper inside the Hotel Horchem under the light of Hitler Jugend torches that had been discovered in the basement. They were under pressure from V Corps to evacuate the town, but managed to resist this notion at least partly due to the certainty that Monschau like Kalterherberg would have been roundly pillaged. “One shooting; two looting,” went the joke. 9th Infantry Division, now arriving in town, had shown that tendency.

Von der Heydte wounded-captive

Still, with reports of a large-scale German parachute operation in the vicinity, by 20 December, the nervous tension in Monschau reached a fever pitch for both panicked civilians and the military government alike. Elaborate searches began of the woods and swamps between the town, Eupen and Malmédy. The operation to flush out von der Heydte’s men in hiding consumed the 18th Regiment of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division and a Combat Command B of the 3th Armored Division. “American soldiers were seeing German paratroopers behind every bush.” In Monschau itself a fruitless house-to-house search began on the night of the 21st. Even if none were immediately found, that disappointment was not to last.

Then in the late afternoon, the three men awoke to plod down toward Monschau crossing the Rur River. But now, reaching the edge of the village and finding no friendly forces– American soldiers only– von der Heydte stopped in disappointment. Barely able to walk, he couldn’t continue. He insisted the other men go on without him around Monschau and seek German lines. He would just hold them up. Only with his direct orders, did they leave their Colonel hiding in the brush. Shivering in wait until dark that Thursday evening of 21 December, von der Heydte finally got to his feet and staggered ahead into town. At 11 PM, the Baron pushed the doorbell of one of the first house he came to in Monschau. It was a squat two story structure with a slate-covered dormer roof at Monschau at Am Oberer Kalk 6 just west of the main road.

Hearing the doorbell, 56-year old schoolteacher, Karl Bouschery found an ailing German officer outside the lattice work door. The man was shivering and hurt; Bouschery led the man inside, supporting one shoulder. Baron Von der Heydte promptly collapsed in the warm kitchen to the wooden floor. The family gathered around him by the glowing wood stove. Bouschery had himself been in the trenches in World War I and although everyone in Monschau had watched the tanks surge triumphantly through the town in 1940, four years later he was disparaged the war and the NSDAP. When the family was able to speak to Von der Heydte, he seemed to feel the same way. “I’m sick and too weak to fight,” he said. He was on the verge of pneumonia. “In the morning I will surrender.” The Baron drank the ersatz coffee made from wheat berries the family fed him, but was too sick to eat any food. Eugene was trained in first aid and splinted von der Heydte’s broken fingers with tongue depressors.

Admiring the von der Heydte’s camouflage uniform, Eugene, proudly announced he was a Jungvolk, even though the Americans now controlled the town. Von der Heydte said nothing and weakly asked for pen and paper. He was fed up with the war. Although he had at first agreed with Hitler’s regime, he now knew it was rotten down deep. All the Jews had vanished from Low Bavaria to disappear into extermination camps in Czechoslovakia and Poland. The proud army he had once fought for was now virtually destroyed. If ever allegiant to Germany, he was still fighting for Hitler; he scribbled a note:

22 December

“To the American Commander of the Military Government of Monschau,

Dear Sir,

I tried to meet German soldiers near Monschau. As I could find there no German troops, I surrender because I am hurt and ill and at the end of my physical resources. Please be kind enough to send a doctor and ambulance because I cannot go further. I lie in the bed of Herr Bouschery and await your help and orders.

Yours sincerely,

Freiherr von der Heydte

Obstl Commando of the German Fallschrimjäger trooops, region Eupen – Monschau.”

The paratroop officer was running a fever of 40 degrees Centigrade. The family put him to bed on a sofa by the stove and covered him with blankets. He fell asleep to the melodic ticking of the family clock. On the morning of 22 December 1944, young Eugene Bouschery took the letter to the Hotel Horchem in town where he knew there were some Americans. There, Captain Goetscheus was electrified by the news. Here in his town was the head of the German parachute operation and he was surrendering! Goetscheus excitedly took the note to the Monschau Postamt to the headquarters of the 47th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division.

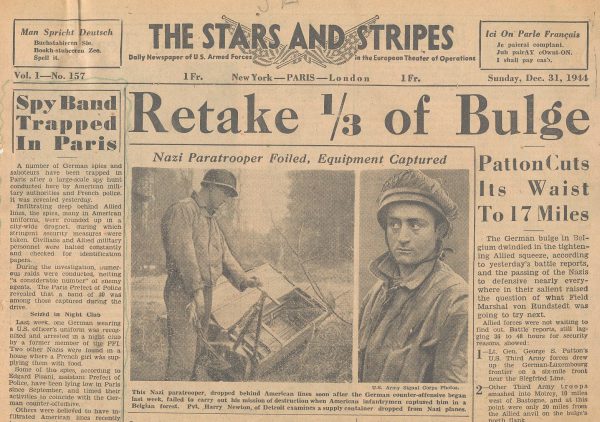

Soon Lt. Col. Lawrence Q. Langland, of headquarters 9th Infantry Division, left in a jeep with an American doctor, a crewed ambulance and several jeep and a halftrack of heavily armed GIs. Yet reaching the Bouschery home at 9 AM and entering “with great drama,” Langland and the others went in to find von der Heydte hardly a threat. He was very ill. Shortly after, being examined by the doctor, he was loaded onto a stretcher, the American GIs posed with the captured Baron. By 10 AM, von der Heydte, was on his way to the headquarters of the V Corps in Eupen.

Still, U.S. Army interrogators the following day found von der Heydte a tough prospect, security minded and intelligent. And if fed up with the unsavory war, he still oozed with arrogant allegiance. Industry in his country had de-centralized, he told his interrogators. “You can destroy our cities, but it is impossible to destroy German industry.” He opined the war would continue for a long time “until a stalemate is reached on the Western Front and the Allies finally come to realize that the real menace to civilization is Bolshevism.” The war still could be won he said because “we are smarter than you are.” The final word from von der Heydte to his interrogators was humorous and cocksure. He was exhausted and had to sleep, but reminded his captors, “Should you hear over the radio that I received the Schwerter zum Ritterkreuz,” he told those taking notes, “please notify me.”

If that confrontation seemed arrogant, as Christmas time drew near in Eupen, the very Catholic commander, known to some of his men as the “Rosary Fallschirmjäger,” showed a softer side:

“There, an officer asked me if I wished to confess. And I thought, ‘My goodness, now at the end I shall be shot!’ But it was only an American Chaplin and because it was Christmas night, he asked me if I wished to confess and take the communion.”

That same Christmas Eve, Freifrau Gabriele von der Heydte was at her home at the Schloss in Egglkofen in Upper Bavaria. As always, she and her brother listened to the news on the BBC at noon. They spoke English and it was a way of getting news from the war without Goebbel’s propagandistic varnish. As it was Christmas Eve, the whole family now gathered that day in the dining room to listen. There was startling news with a south London accent: “BBC reports that the Lion of Carentan, Colonel Friedrich von der Heydte, was taken prisoner by U.S. forces in the Ardennes yesterday….” There was a collective gasp– then tears. He was alive and safe. Gabriele was beside herself with joy, vowing more prayers at high mass that holy evening. “It was the very best Christmas gift of my life,” she would later say.

At Hitler’s bunkered headquarters near Ziegenberg, there was no such good feeling. “No further word from Gruppe von der Heydte,” OB West reported ominously. What von Runstedt’s intelligence service did report was a steady stream of American reinforcements pouring into the Ardennes from the north. The 3rd Armored Division was now chasing down German paratroopers in the woods south of Eupen and putting a clamp-like squeeze on Kampgruppe Peiper in La Gleize. Looking over the red map symbols crowding the right flank of his great offensive, Hitler insisted someone find who was responsible for the oversight. He had seen the danger from that sector.

“Where are the Jagdtigers?” the German leader demanded to his household military staff. It was a typical question; from the Führer who was always obsessed that last muscular unit in any fight that might tip the military balance. Hitler had intended schwere Panzerjäger Abteilung 653 to help the Volksgrenadiers seize Monschau and push on to establish an armored cordon behind their 128mm guns to rope off the northern flank in the Ardennes below Aachen. That would protect Peiper’s dash to the Meuse.

Some time went by, with phone calls made, but presently the Gen Jodl’s Luftwaffe adjutant moved up to the map room. “A check has been made,” Herbert Büchs began, “and the trains bringing the battalion forward have been blocked by attacks on rail lines.” The nine available Jagdtigers had not even crossed the Rhine River, although over a dozen more of the 77 ton juggernauts just off production were joining Maj. Rudolf Gillenberger’s battalion although scattered across the Reichsbahn. Hitler was flummoxed; no he was furious. Büchs gave him wide berth. “They must be mad!” the German leader cried shaking his head, “If the enemy attacks us with a dozen heavy tanks, everyone is screaming. But when we have 24 of the heaviest tanks in the world, they aren’t even used!”

Not that it mattered now; von der Heydte had been vanquished from his blocking position, his paratrooper battle group completely scattered and destroyed. At the close of the day, Jochen Peiper and the full panzer strength of the Führer’s namesake Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler was out of fuel and ammunition– totally surrounded by American tanks and infantry flooding down from the north.

Wacht Am Rhein ebbed and faded. Even the Ardennes star of Jochen Peiper flickered uncertain. The Waffen SS King of the blitzkrieg was now turned back, even hunted and warily circled.

[/read]