The post A French Tragedy appeared first on World War Media.

]]>Arrested as a Jew under the racial laws, Novelist Irene Nemirovsky, died at Auschwitz at the age of 39. Successful in her day, she is now best known for the posthumously published Suite française. How France sent its greatest chronicler of the Nazi occupation to her death.

By Alex Kershaw – Author of ‘The Bedford Boys’, ‘ Avenue of Spies’ and ‘The Liberator’

“In life, as on a shipwrecked boat, you have to cut off the hands of anyone who tries to hang on. Alone, you can stay afloat. If you waste time saving other people, you’re finished.”

Irene Nemirovsky, author of Suite Francaise.

On 11 July 1942, 39-year-old Irene Nemirovsky walked alone through beautiful countryside near Issy-l’Eveque, a village in the Bourgogne around two hundred miles south of Paris. Her home was a large building near a former livestock building in the village, just a short walk from the local police station. She had a wonderful view of the Morvan hills. Her husband, Michel, grew beetroot and other vegetables in a large garden nearby and so she and her two daughters had not gone hungry.

The Russian-born writer was a striking woman with large, highly intelligent eyes, her dark hair usually pulled back from her broad forehead. That day, she felt unusually carefree, her sense of dread and doom having abated. She had been forced to write these last months in minute lettering because of a shortage of paper and was near completing what would be her masterpiece, to be titled Suite Francaise. But as a Jewish author she could no longer publish her work and she had little hope, if any, of ever seeing it in print. Nor could she ride a bicycle or take a train to her beloved Paris, which she had fled in 1940 just ahead of the German advance.

She had recently been reading the journal of the writer Katherine Mansfield and had noted certain lines that matched her own mood: “Just when one thinks: “Now I’ve touched the bottom of the sea – now I can’t go down any lower,” one sinks deeper still. And so on for ever.” But she did not feel that way today, 11 July 1942, as she walked in the woods near her home. Pine trees towered above her as she down on her blue cardigan, which she had laid on a dank blanket of rotting leaves. She had a copy of the novel Anna Karenina and an orange in her bag. She listened to a steady drone of honeybees. Later that day, she would pen her last words in a letter to her editor in Paris: “I’ve written a great deal lately. I suppose they will be posthumous books but it still makes the time go by.”

Two days later, on Monday 13 July, the weather was again superb. It was around 10am when a car stopped in the Place du Monument aux Morts in Issy-l’Eveque. There was the sound of footsteps then a knock on the door. Two French policemen had a summons with them. Irene’s two children were with her and her husband. One was called Denise. She heard her parents go into their bedroom. Irene asked her husband to do all he could to secure her release through contacts with important people in Paris, those with connections to the Germans, especially high profile collaborators. There was a “dense silence”, recalled Denise, and then the gendarmes allowed her to kiss her mother goodbye. Irene threw a few things into a suitcase. Her voice frail, she told her children she had to go away for a while. Denise looked at her father. He was clearly very upset but he did not cry. Finally, Denise heard a car door slam shut and then the “dense silence” returned.

Irene was taken to a police station at Toulon-sur-Arroux, ten miles away. The next day, Irene wrote to her husband: “If you can send me anything, I think my second pair of glasses in the other suitcase (in the wallet). Books, please, and also if possible a bit of salted butter. Goodbye, my love!” Before they could be arrested, Irene’s children, Denise and Elizabeth, were taken to a safe house. They would miraculously survive the war. Meanwhile, Michel contacted anyone who might be able to help him secure Irene’s release. He was convined that some of his contacts, such as Rene de Chambrun and other “influential friends”, would exert pressure and save his wife.

The following evening, 14 July, Paul Epstein, Irene’s brother in law, had a face-to- face meeting with a prominent collaborator, a corporate lawyer called Rene de Chambrun, in Paris. It was Bastille Day but there had been no national celebration. Two days later, Epstein was in turn arrested. Andre Sabatier, Irene’s editor, tried to contact Rene de Chambrun, calling him urgently on the phone several times. It is not known if Rene returned any of the calls.

Paul Epstein was one of thousands caught up in the mass arrests that came to be known as the Grand Rafle, which began on the night of July 16 and lasted well into the following day as 13,152 Parisian Jews, including 4000 children, were arrested and around half of them taken to the Vel d’Hiver, a large velodrome beside the Seine. The round up, carried out with great efficiency by the French police, was the only thing people all over the talked about, it seemed, in every food line, office and hospital ward. The screams of Jews committing suicide pierced the terrible quiet in some quartiers. The famous German writer, Ernst Junger, serving in Paris, noted with matter of fact precision in his diary that he had heard “wailing in the streets” as families were literally torn apart, with adults being separated from their young children.

The medical conditions at the Vel D’Hiver, it was soon learned, were utterly atrocious. There were no lavatories. There was only one water tap for over seven thousand people. According to one account: “It was a rafle conducted in keeping with the best of French conditions, for at noon the policemen returned to their posts to have lunch while higher-ranked and better paid set off to nearby restaurants. Only after the sacred dejeuner could the manhunt continue.”

Women’s cries could soon be heard throughout the Vel D’Hiver. “On a soif!”

“We’re thirsty!” they called out.

Only two doctors were allowed inside the Velodrome, equipped with little more than aspirin. After five days, those incarcerated were transferred in cattle trucks to camps at Pithiviers, Beaune-la-Rolande and Drancy, a modernist high-rise development built in the 1930s also known as La Cité de la Muette – the City of Silence.

A young Parisian called Annette Monod watched a batch of young children, who had been separated from their parents, as they were taken by French police from the City of Silence: “The gendarmes tried to have a roll call. But children and names did not correspond. Rosenthal, Biegelmann, Radetski – it all meant nothing to them. They did not understand what was wanted of them, and several even wandered away from the group. That was how a little boy approached a gendarme, to play with the whistle hanging at his belt: a little girl made off to a small bank on which a few flowers were growing, and she picked some to make a bunch. The gendarmes did not know what to do. Then the order came to escort the children to the railway station nearby, without insisting on the roll call.”

On 27 July, Irene Nemirovsky’s husband Michel wrote a letter to German ambassador in Paris, Otto Abetz: “I believe you alone can save my wife. I place in you my last hope.” To make sure the letter was delivered to Abetz, Michel sent it to his wife’s editor in Paris, asking him to pass it on to Rene de Chambrun for forwarding to Abetz. The next day, Irene’s editor duly sent the letter to Chambrun who may or may not have passed it on.

Meanwhile, along Avenue Foch and elsewhere, trucks loaded down with furniture and other Jewish possessions could be seen after deported Jews’ homes were ransacked. The looters belonged to the Einsatzstab Rosenberg, actually headquartered on Avenue Foch. Eventually, according to the Nazis, this looting saw 69,619 Jewish homes, 38,000 of which were in Paris, “emptied of everything in daily or ornamental use.”

At the end of July, after over 14,000 Parisian Jews had been rounded up, the Catholic Church in Paris made a belated appeal to Pierre Laval on the children’s behalf. But the Vichy premier was adamant: “They all must go.” And they did. Less than four percent of those sent to the east returned. Not one was a child. Those responsible for this genocide later claimed they had no idea that the deportations were in fact to death camps, not some mythical Jewish haven.

It was a shameful time for France, especially for those who had actively collaborated with the SS and Gestapo. Their new German friends were part of something monstrous – the mass murder of their fellow French citizens. It was impossible to pretend one did not know what was happening. Indeed, those with the best connections to the Nazi regime found themselves begged by relatives and others to do something given their influence. At the height of the deportations, Josee Laval, the wife of Rene de Chambrun, was fully aware of the tragedy. She received two letters asking her to help save Jewish friends of friends. Yet she remained utterly self-involved. On the first day of the round up, she had complained in her diary that her beloved father, Pierre Laval, the head of the Vichy regime, was “too busy” to have dinner with her. She did not mention why.

Her husband was as guilty of inaction as Josee. He had been begged in person to help save Irene Nemirovsky. He had the power to do so given his close connection to German ambassador Otto Abetz who had allowed the Vichy official Fernand de Brinon’s Jewish wife to avoid deportation in 1941. Indeed, with the right connections, it was possible to buy or trade anyone’s release. And he knew it. Rene also counted the smooth-talking Rene Bousquet, head of the French police, as an old friend, having belonged to the same rugby team in his youth. Yet there is not a shred of evidence to indicate that Rene took take up Nemirovsky’s case with either Abetz or Bousquet.

It was later learned that Nemirovsky, listed as “a woman of letters”, was deported from France on 16 July 1942 along with 119 other women. Her train had left promptly at 6.15am and arrived on 19 July at Auschwitz. Aged just 39, the author or the finest novel of the German occupation, Suite Francaise, breathed her last after just four weeks at the death camp. Two months later, the US government offered to provide refuge to a thousand Jewish children whose parents had, like Nemirovsky, been deported. Pierre Laval insisted that only “certified orphans” could leave for the US. Since nothing was officially known of the fate of the deported parents, the children were not allowed to go to the US. Most would die in the gas chambers. Nemirovsky’s husband, Michel Epstein, fared no better. He was arrested on 9 October 1942 and sent to Auschwitz. As with 77,000 other Jews in France, he would never return.

The post A French Tragedy appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post U.S. Mortars of World War II appeared first on World War Media.

]]>

When history is visceral and experiential, it is typically more compelling and engaging than when it is taken out of the human context. The subject is notorious for being presented in dry and uninteresting ways, but that is mainly because most people are exposed almost exclusively to the sterility of classroom lecture. When it comes to the history of the Second World War, classroom instruction is critical to understanding the big picture of the conflict, but bringing clarity to the individual soldier experience is something that is typically best edified by good old-fashioned fieldwork.

by Martin K.A. Morgan and very special thanks to Brian Domitrovich

This can be done by visiting a battlefield or, in some countries, by live-firing the weapons used in a given war. As described in my January 22, 2017 post about shooting the German MG.42 machine gun, a day at the range can offer a powerful and memorable insight into the lives of those who experienced combat first hand. But even in the U.S.A. where it is possible to own just about every type of weapon used in ground combat between 1939 and 1945, one category is usually missing: mortars. Each country involved in World War II used them to great effect in circumstances where indirect, high-angle fire was needed but field artillery fire was unavailable. They were dangerously accurate, and they could operate in rain or shine – in the blistering heat or the numbing cold.

Despite their prolific use and significant importance to the story of World War II combat, most American collectors do not own mortars, and as a result they are largely only understood in the abstract. We read technical details about weight, range, accuracy and explosive power, but we just do not have access to them like we have access to rifles, pistols and machine guns. For that reason, I recently traveled to western Pennsylvania for a day at the range with Brian Domitrovich, owner of three live U.S. World War II mortars: a 60mm, an 81mm and a 4.2-inch. Brian’s possession of these weapons is regulated by the National Firearms Act of 1934, which designates them as “destructive devices” and holds him up to stringent qualifications for their ownership.

For him to be eligible to purchase these registered destructive devices, Brian had to be a U.S. citizen over the age of 21 with no criminal arrest record, he was required to pay a one-time $200 transfer tax for each weapon, and he had to wait between six and twelve months while each transfer application was reviewed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (the “BATFE”). In other words, the 1934 National Firearms Act created a heavily regulated category of civilian ownership that Brian qualified for, thus allowing him to make it rain 60mm, 81mm and 4.2-inch mortar rounds. We hauled all three weapons out to the Beaver Valley Rifle and Pistol Club near the township of Patterson Heights, Pennsylvania and spent the day putting each tube through its paces.

For each mortar, we fired only inert projectiles – meaning that only propelling charges were used and none of what we fired exploded downrange. The only partial exception was the M2 mortar, through which we fired BATFE-approved 60mm reusable training projectiles made exclusively by ordnance.com. These projectiles are equipped with a proprietary fuze assembly that produces a non-lethal impact explosion through the use of a point-detonated 20-guage blank shotgun shell. Although they do not distribute deadly fragments, they do produce a report downrange that simulates the experience of shooting a 60mm M49A2 high explosive round.

The smallest and lightest of the three mortars being demonstrated that day, the M2, consists of a 12.8-pound tube, a 16.4-pound bi-pod/mount, and a 12.8-pound baseplate. With an overall 42-pound weight, the M2 gave U.S. fighting forces during the Second World War the kind of handy mobility that made it easy to provide company-level fire support, and even advance with an attacking echelon if necessary. Although it can deliver concentrations of fire to a maximum range of 2,000 yards, we had to keep our rounds within 200 yards so as not to lose any of the five-pound reusable training projectiles. When we went downrange to recover the rounds, they were all sticking out of the ground like lawn darts within a few feet of each other.

Moving up in size and weight, we fired the 81 mm M1 mortar next, but the space constraints at Beaver Valley Rifle and Pistol Club prevented us from realizing that weapon’s full range potential. With a full increment charge and a 6.87-pound M43A2 high explosive round, the M1 mortar could hit a target almost 3,300 yards away, giving it a significant range advantage over the 60mm M2 mortar. Using a minimum propellant charge, we were able to keep all of our 8-pound, 81 mm projectiles in one area but they still dug deeper into the ground than the lighter 60mm projectiles did. The M1’s greater capabilities come with a cost though: greater weight. With a 44.5-pound tube, a 46.5-pound mount, and a 45-pound base plate, the total package is almost 100-pounds heavier than the 60mm mortar.

Despite its weight though, the 81mm mortar was an important part of the Table of Organization and Equipment of U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps maneuver battalions throughout World War II. It was even a tool used by airborne units, and was dropped in parachute bundles during Operations Neptune, Market Garden, and Varsity. Ground combat units appreciated the 81mm mortar because of its mobile and hard-hitting qualities, and that is why it occupied a prominent place in the arsenal of American fighting forces during the Second World War.

Last but not least, we fired the mighty 4.2-inch M2 chemical mortar. Developed before World War II as a means of delivering toxic agents (thus the name “chemical mortar”), the U.S. Army Chemical Weapons Service eventually turned the 4.2 into a weapon capable of delivering high-explosive fire. But TNT, and Mustard Gas rounds were not on the menu for our live fire exercise, so M335A2 Illuminating Rounds were used instead. Weighing 17-pounds each, they tumbled through the air like parabolic watermelons and half-buried themselves in the mud at the very edge of the designated long-range lane. While convenient for our purposes, the M335A2 rounds need the weight of the illuminating chemicals in them to stabilize in flight. The ones we fired that day were inert and (therefore) empty, so there was only so much the barrel could do.

Unlike the 60mm and the 81mm mortars, the “four deuce” uses a rifled barrel to stabilize its projectiles in flight, and those projectiles engage that rifling through the use of a brass obturating plate. While the barrel did its job with no problem and the rounds caught the rifling as they were designed to, after leaving the tube’s muzzle at 700 feet per second they gradually lost their stability and started to tumble. Still, it was lots of fun throwing them skyward in an offering to the spirit of Saint Barbara. Once again though, we had to generate as little range as possible, which was not an insignificant challenge with the “four deuce.” That weapon can throw a round out to 4,400 yards (2.5 miles) and we had only 300 yards to play with, so we were barely scratching the surface of what that tube could do.

Weighing-in at 333-pounds overall, the “four deuce” is a beast of a weapon. Just to put this in perspective, it weighs the same as eight 60mm mortars or two and a half 81mm mortars. It’s base plate alone weighs as much as I do, which only became an issue when we had to carry it up the stairs from Brian’s basement to get it to his truck. Every bit of that effort was worthwhile though because it offered a priceless opportunity to appreciate the difficulty of manhandling this weapon that contributed so meaningfully to allied victory in World War II. The 4.2-inch mortar fought for the first time in the Sicily campaign in 1943 during which it fired over 35,000 rounds in 38-days. It then went-on to fight it’s way across difficult terrain in Europe and islands in the Pacific.

The Army used it, the Marine Corps used it, and even the U.S. Navy used it on landing craft converted into mortar gunboats under the designation LCI(M). Though it never delivered a gas attack in combat, it did put down vast quantities of TNT and smoke during World War II and again during the war in Korea. Having the chance to shoot the “four deuce” – alongside its 60 mm and 81 mm cousins – provided the kind of visceral and tactile experience that I value because it helps bring another element of the story of World War II into sharper focus.

The post U.S. Mortars of World War II appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post Tank Training Site in England appeared first on World War Media.

]]>Fritton Lake and the surrounding land was used by the 79th Armoured Division as a training and experimental site from 1943 through to 1947. It was used to secretly develop techniques and to instruct tank crews in the operation of amphibious tanks, known as Duplex Drive or DD Tanks, primarily for use in the allied invasion of France during World War 2.

by Stuart Burgess

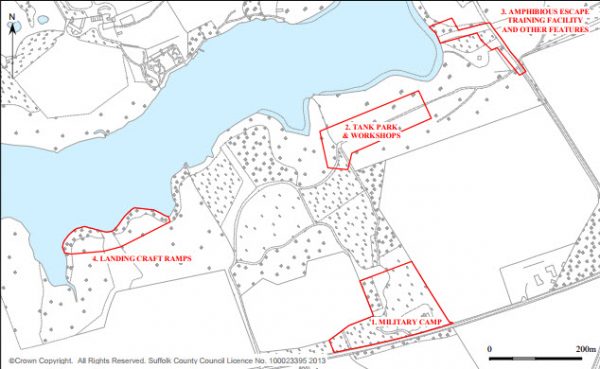

It originally consisted of an accommodation area, workshop and maintenance buildings, dummy landing craft slipways, specific training structures, a large tank park and numerous tracks and roadways linking the various components.

Due to the secret nature of this establishment relatively little is known about its layout and operation. Following its decommissioning, the site was cleared and the majority of above ground structures demolished. Despite this, significant evidence is preserved at this site in the form of foundations, floor slabs, track ways, and areas of hard-standing as well as the structural remains of the landing craft slipways. There is also at least one extant building with significant portions of a second standing nearby. Many of these remains are relatively slight and are in danger of being destroyed or simply being lost. To mitigate against this and as an aid to further the understanding of this site, a survey of all the known extant remains was carried out. The main the aim of the survey was to produce a plan of the training establishment and to undertake a basic descriptive record of the remains.

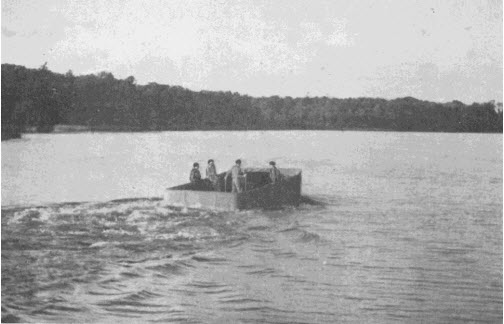

The area around Fritton Lake, situated in the Suffolk parish of Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet (formerly three separate parishes, now a single entity), was used by the 79th Armoured Division of the British Army, during the 1940’s, for the development of amphibious tanks and as a training establishment for crews to familiarize themselves with their use. The main drive behind the training program was the proposed D-Day landings, which comprised a significant part of the Allied invasion of Europe leading to the end of World War Two. The amphibious tanks were known as DD Tanks, which stood for ‘Duplex Drive’ and was a reference to the tank’s twin drive system needed to incorporate propellers for use when floating. The act of using the tank on water was known as ‘swimming’ and they were often confusingly referred to as ‘swimming tanks’.

The site was in use until 1947 after which it was dismantled and the site returned to the original owners. Part of what had been an area of accommodation for men based at the site, including at least two extant buildings, was leased to the Scouting Organisation for use as a Scout Camp. The remainder of the land was restored and replanted as cover for game birds or returned to forestry. The entire site then lay undisturbed and virtually forgotten until the early part of the 21st century when the then Country Park Manger of the Somerleyton Estate, Stuart Burgess, recognized that significant components of the camp survived within the woodland on the south side of the lake and undertook a program of personal research and investigation into the site’s history with the ultimate aim of bringing recognition to the site’s historical

significance and to further understanding of the important role it played in World War Two. Although numerous remains are present scattered across the area, no attempts to assess the extent of the site’s survival had been undertaken. In order to rectify this, funding was obtained from the European Interreg IV A Project to undertake a basic survey of the extant remains.

Valentine and Sherman Tanks were adapted to make them amphibious, so that they could “swim” to shore and provide close fire support to the first wave of troops landing on enemy beaches. These tanks were part of a series of tanks that had been modified to do something more than just fight in the regular way, and were collectively known as “funnies”. The Lake became a significant training facility in 1943 and went on to train in excess of 2000 men prior to D Day and a further 500 after D Day. The DD tanks and their crews proved themselves as key and effective weapons for the D Day Landings, and as such became versatile in subsequent European Operations associated with Estuary and River crossing.

The significance of the Freshwater Training Wing cannot be underestimated in relation to the development of the Duplex Drive Tanks. Its archaeology concerns the Military Camp and functional infrastructure associated with the provision of elementary training, tactical development, amphibious tank escape as well as post war experimentation and trials. The 60 acre site is well preserved, with surviving features such as a tank park, contemporary Landing Craft slipways, subterranean structures and the footings of a large number of huts, stores and other buildings connected with the workshop and maintenance facility.

Two regiments – the 15th/ 19th Hussars and the Staffordshire Yeomanry undertook training at Fritton in preparation for their role in crossing European rivers with the DDs. As it transpires only the Staffordshire Regiment eventually undertook River Crossing Training at a special wing at Burton upon Stather, before undertaking European Operations with their DD tanks. During these operations it became evident that the heavy Sherman DDs encountered difficulties exiting the soft silty riverbanks, and to this end Fritton – as well as Burton upon Stather – assumed a secondary role – that of overcoming river obstacles. Additionally at this time, the 79th Armoured Division were being replaced by the Assault Training and Development Centre (ATDC). Research and trails continued at Fritton for a further 18 months under ATDC, before they were replaced by SADE – Specialised Armour Development Establishment.

Training continued at Fritton under SADE until 1947, where upon swimming tanks were becoming larger and more impractical to be launched at sea. A facility continued at Gosport for a number of years, and by 1951 that too was eventually closed. Infrastructure at Fritton was removed by 1950 and the woods and lake returned to the Estate. Part of the military camp was leased out to the Scouting Organisation, and the remainder of the land was replanted as cover for game birds and forestry.

Thus Duplex Drive Tank Development came to an end. Its role on D Day was a unique and significant. As a weapon hurriedly devised and tested during WWII it proved its effectiveness as a dual purpose vehicle. Every credit should go to the men who developed, trained and ultimately operated these tanks, many of whom were present at Fritton Lake from 1943-1947.

Photo by Jo Segers

The post Tank Training Site in England appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post From Gliders To The Bois Jacques appeared first on World War Media.

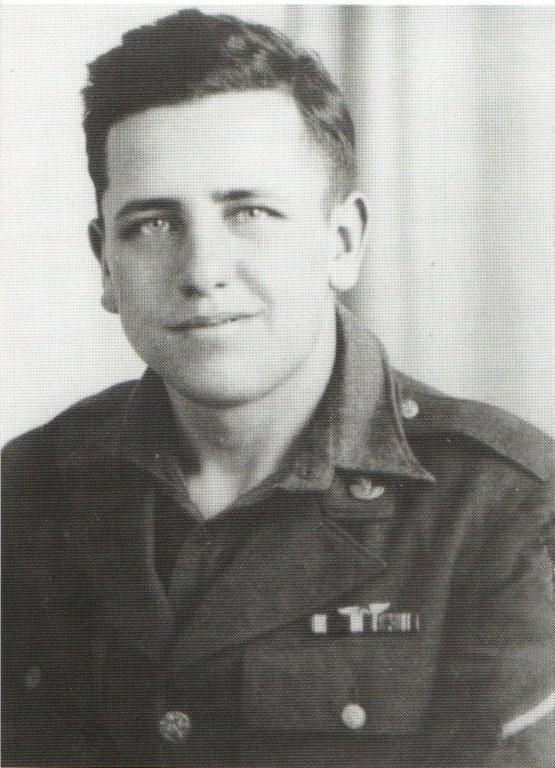

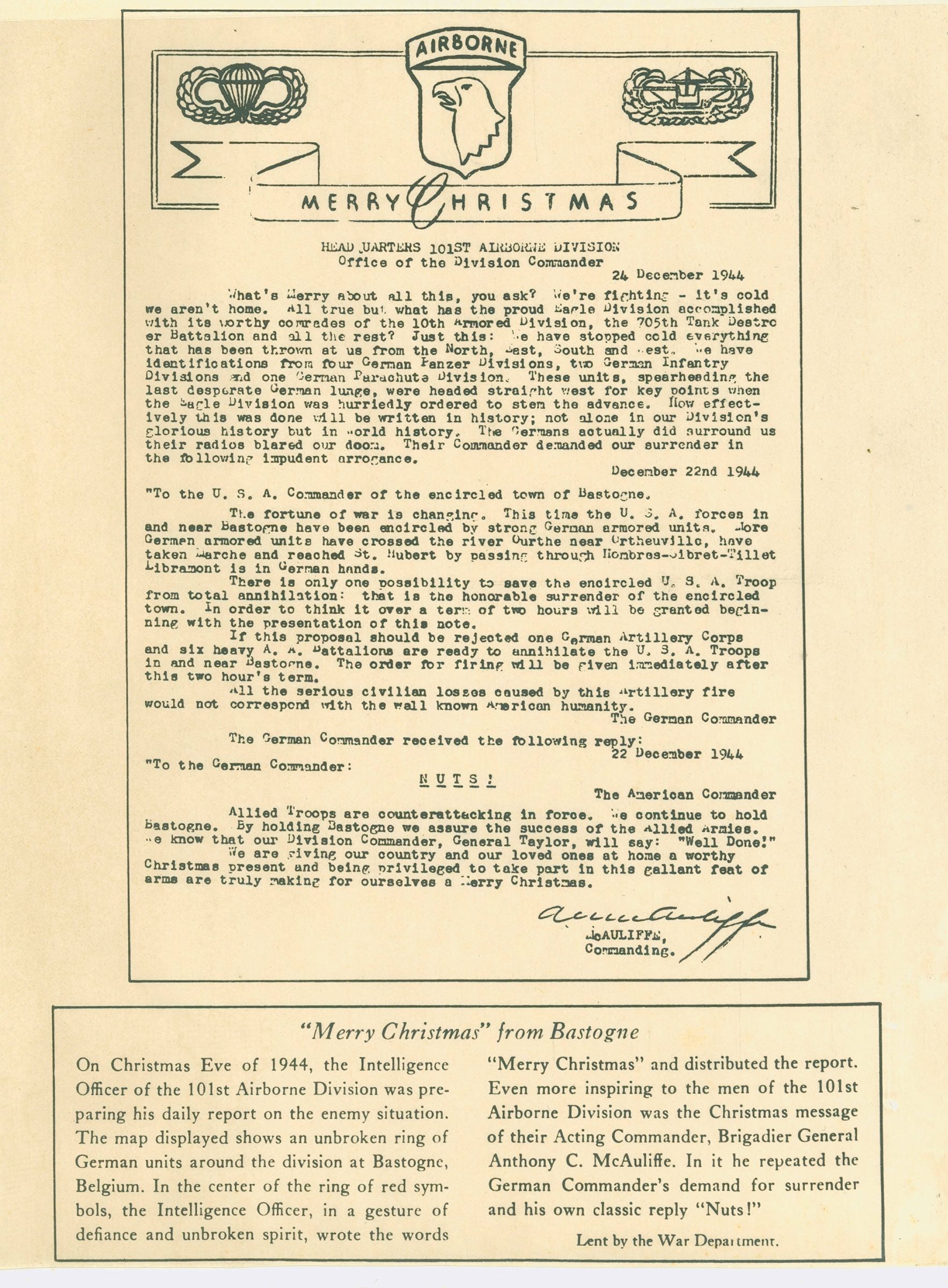

]]>It’s a grainy, relatively unknown photograph of a bunch of dirty, unshaven soldiers standing around a makeshift Christmas tree in the middle of a snowy field. Taken “somewhere near Bastogne”, little else was known about who was depicted and how they came to be in that field. But slowly, the story behind the picture started to come together after a sizeable amount of research and bit of consultation. The men featured were members of the 81 mm Mortar Platoon, Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, and the man that became the linchpin to the story behind the photo was Hugh “Ben” Rous. This is the winding journey of Ben in World War II.

Ben, a native of Avery, Idaho, was scooped up by the draft like a lot of men after the attack on Pearl Harbor. “The Adams County draft board ordered me to go to Milwaukee for examination on Dec. 3, 1942. I went along with a bus-load and since I was still breathing, passed the ‘physical’ exam and was put on class 1-A.” After initial processing at Ft. Sheridan, Illinois, Ben was sent to Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, to join the 82nd Airborne Division’s 326th Glider Infantry Regiment.

Ben completed his basic training at Ft. Bragg, and afterwards, he and the other members of the 326th were transported by train to Alliance, Nebraska for another grueling round of training. While in Alliance, Ben was assigned to an 81 mm mortar platoon and repetition became the platoon’s the catchphrase. “We took the gunner’s tests and observers tests time after time. We also took many, many glider rides.” As they trained, the men couldn’t help but notice that the rate of attrition for young officers was quite high, with 2nd lieutenants seemingly arriving and leaving almost the same day. As a result, Ben and his fellow glider riders often joked that the purpose of their training was to “train officers.”

After training stints back at Ft. Bragg and then at Camp Mackall, the 326th readied itself for movement to England. Many senior Allied leaders feared that there would extensive casualties among the parachute units during the invasion of Normandy and felt it was necessary to reinforce those units. As a result, many of the 326th troopers received transfer orders to paratroop units once they arrived in England.

While Ben wasn’t one of those transferred, he eventually volunteered for the paratroops as well. “Our willingness was immediately seized upon and off we went to Jump School (in England)!” After completing the training Ben received his Parachute Wings. “Along with being (awarded) one of the most prestigious badges in the services, I started collecting the famous “Jump-Pay” of an extra $50.00 a month for hazardous duty… we had gotten out of the “flying coffins” (and we were) happy to be in that special group. We wore our new “Wings” very proudly,” said Ben.

Ben received orders assigning him to Company E, 506th PIR. After arriving at their billeting area of Nissen Huts and horse stables, he reported to the company commander, Captain Richard Winters. The youngish looking captain, in reviewing Ben’s service jacket, noticed that he had qualified expert on the 81 mm mortar. “He asked me if I preferred being in a mortar platoon. My thinly restrained reply was, “Sir, if you had trained constantly for 18 months in 81‘s where do you think you would prefer to be?’ His reply was, I’ll talk to the Hq. Co. Commander, and if he needs a mortar-man, I’ll transfer you”. It would not be the last time he would serve under Captain Winters.

“So with that (transfer) I had found a “home” in the Hq. Co. 2nd Bn., doing the things I had spent all my time up to now training for…I also learned some combat tricks from these seasoned troopers…the few survivors from Normandy’s battles!” Being several years older than the majority of his fellow troopers as well as married, the men quickly took to calling Ben, “Pop”.

With Ben firmly entrenched in the 81 Mortar Platoon, alerts quickly arrived for the unit to take part in several combat jumps in France. “We actually got sent to Airfield Marshaling areas and scheduled for missions 3 different times. Each time the mission got canceled just before we took off. One time we were totally loaded in the planes, with motors revving up just as the call came down that Patton had already taken the area we were scheduled to jump on and the mission was canceled! What a letdown and big relief in a way all at the same time.”

The letdown wouldn’t last long for Ben. On 17 September 1944, the alert became real. The men would jump into Holland as part of Operation Market-Garden. During the approach to the drop zone, Ben’s C-47 took quite a bit of ground fire. One round hit the starboard wing tip, causing the aircraft to pitch to that side. This threw Ben and the other paratroopers away from the jump door. They struggled to move to the door and literally had to throw themselves out.

Ben’s ‘adventure’ did not end there. He descended rapidly due to his weight and the weight of his attached equipment. That caused him to fall into the top of an orange parachute carrying an equipment buddle. With his heart racing, Ben hurriedly ‘walked’ off the chute and continued his descent. Even his landing ended up giving him trouble. When Ben made contact with terra firma, the butt stock of his M1 Garand rose up and socked him in the chin. He had a sore jaw but at least he was on the ground and in one piece. As he dusted himself off and adjusted his equipment, Ben heard German 88’s firing in the distance.

The sound of those big guns signaled the start of a campaign that began with a number of moves and counter moves as the 506th attempted to keep their portion of Hell’s Highway open for business. The men found themselves marching off like firemen attempting to put out house fires, only to be ordered off to another location to close off German penetrations in a different portion of the highway. During one 24 hour, seesaw period, Ben had three different rifles destroyed by enemy fire and each time he obtained a replacement from a wounded or dead paratrooper.

Finally the seesaw fighting ceased as 2nd Battalion was ordered to The Island. Ben would spend the remainder of his time in Holland firing his mortar in support of the line companies while alternately bailing the water out of his mortar pit. While the conditions were miserable, Ben always remembered the kindness of the Dutch people, especially their willingness to share their meager rations with him and his fellow paratroopers. One of his fondest souvenirs from Market-Garden was a small Dutch flag given to him by a young mother as they approached Eindhoven. He kept that flag right next to a swatch of his parachute that he had cut out after landing. After seventy-six days on the line, Ben and the rest of the 506th, was pulled back to Mourmelon, France to rest and refit. The respite did not last long.

Ben and his buddies had barely spent twenty days in Mourmelon when the alert came. They had been dreaming of passes to Paris and the upcoming Turkey dinner that would undoubtedly accompany the arrival of Christmas. But it was all for naught. His platoon sergeant told them to gather their gear and be prepared to move out. “Grab whatever you can because I don’t know when we’ll be resupplied. “But Sarge, the ‘81’ is still at the armory for maintenance!” It didn’t matter, he said. Orders were orders and the man giving those orders was none other than his former company commander, Captain Richard Winters.

Ben and the other members of his platoon rummaged through their duffel and barracks bags, hoping to find a stray clip of ammo, grenade or K ration. Pockets were stuffed with extra socks. They were critically short of ammunition for their mortar, winter clothing and many other supplies. As they mustered outside the barracks near the cattle cars that would carry them into battle, the men came to the stark realization that they had about five rounds of rifle ammunition per man. This was hardly the ideal way to head into a combat situation.

As they drove through the night, the situation was not lost on Ben and his fellow mortar-men. Thankfully, all hope was not lost due to a bit of happenstance. “The picture was totally bleak already and we hadn’t quite arrived yet! The bright spot, the ONLY bright spot, was that as we went along sometime during the trip, we passed an abandoned jeep with a load of rifle and machine gun ammunition. We finally got some of the precious ammo we needed.”

Sometime after dark, the convoy arrived outside the small Belgian town of Bastogne. They had stood in the back of the cattle cars, huddled together to share body heat, but by the time they arrived the men were cold and stiff from the long, frigid trip. As they attempted to regain feeling in their arms and legs, Ben and the others were ordered to form up into columns. They proceeded to walk towards an open field where they were ordered to dig defensive positions.

The next morning, the battalion was ordered to move into a wooded area that they would come to know all too well over the next few weeks. The name of that forest was Jack’s Woods or the Bois Jacques. Once again, Ben and the others found themselves digging in. “Why the hell are we digging mortar pits when we ain’t got no mortar?”, one of Ben’s platoon mates complained. “Don’t worry…they’ll catch up to us…hopefully before the Krauts come-a-callin’,” was the reply. Hours later, a jeep pulled up bearing their mortar and some ammunition. They were back in business.

On December 23rd, the men received a welcome present…an airdrop of supplies. “The sun broke through and Glory-be, the damn sky was FULL of Allied/American supply aircraft! What a relief! Oh! It was a gorgeous and thrilling thing to stand there in the cold and snow up to your “you-know (what)” and see the equipment bundles full of food, ammunition and at last some winter clothing etc., tumbling out of the planes, the chutes billowing out and their loads whomping down in to the snow.”

In addition to ammunition, food and medical supplies, the men received the gift of warm feet. “As we retrieved the bundles, first we cut up the bag material and wrapped our feet in it, to help keep our feet warm. Then we proceeded to take care of the supplies and ammunition we so sorely needed. How great it was to have warm feet!”

The following day, according to Ben, the German artillery had been quiet and as a result, the men of the platoon decided to celebrate Christmas by trimming a tree. They scrambled to find anything with color…scraps from colored supply parachutes, but mostly they decorated it with strings of foil chaff that had been dropped by friendly aircraft to fool German radar. “Then we put some full and empty ration boxes to represent our presents under the tree. We even used a couple of live mortar shells! For a brief few moments on Christmas each of us was at home with loved ones! At least in our minds!”

Once word spread of their tree, Regimental Headquarters sent a photographer down to take their picture. The platoon gathered around the tree, with Ben kneeling at the far left. The other men featured in the photo were: (Kneeling, left to right) PFC Hugh B. “Ben” Rous, PFC Wilford J. Grant, PVT Stanley L. Hagerman, T/5 James G. “Jim” O’Leary, (Standing, left to right) PFC John C. Joyal, SGT Wyndell E. Russell, S/SGT Charles L. Roeser, PFC Darce K. Hardin, PFC Nicholas J. “Nick” Blahon, Joe MacKorn, K. Chidden, S/SGT Norman A. Jorgensen, PFC Lincoln F. Keeler Jr., PFC Joe C. Trujillo, PFC Harry A. Gibson, PFC Steve Mihok, unknown Reg HQ man.

After all the excitement of the photo opportunity had died down, the platoon got back to their ‘normal’ routine in the woods. They fired in support of several patrol actions for the next 10 or so days until they received the order that they would be moving out. After Company E and elements of 3rd Battalion cleared the town of Foy, Ben and the mortar platoon moved up towards the town of Noville.

“We had started to dig a mortar emplacement and some foxholes. Suddenly I dove into my foxhole going in headfirst. I don’t recall ever going in head first before, but it was lucky I did because I caught a fragment from a “screaming meemie” right through my calf of my leg. Later it was described as a two and one half inch by six and one half inch wound! I recall thinking that it was a good thing I had gone in head first…what if my neck had been sticking up there?”

Ben’s quick-thinking sergeant, a man named Leland Peterson, got on a field phone and called for a medical jeep to come and evacuate his stricken mortar-man. “We hadn’t seen a vehicle for days it seemed. Suddenly there it was! Ready to evacuate me to Bastogne proper which was only two miles way. Later on I was moved to an evacuation hospital near Paris. Finally, I had my pass to Paris and dang it, here I was with only one good leg! Oh, the cruelty of war!”

Ben’s stay in the hospital took him from Bastogne, to Paris and then to England on January 21st. He boarded a ship in late April 1945 and by May 13th, he was back in the States. Ben Rous had come a long way to get home. Throughout it all he kept a smile on his face and that smile can still be seen in a relatively obscure photo of a group of dirty soldiers gathered around a Christmas tree in the snow.

Ben Rous passed away in 2007 and was active in both the 82nd Airborne Division and 101st Airborne Division association’s right up until his death. He was buried with full military honors.

The post From Gliders To The Bois Jacques appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post Dunkirk From The Air appeared first on World War Media.

]]>By May 26 1940, around 250,000 British troops, the rump of what remained of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), were surrounded in the French port of Dunkirk and being mercilessly attacked by Göring’s Stuka dive-bombers. From the air it seemed that the nearby beaches swarmed with a huge army of ants that rippled with fear as German pilots made strafing runs.

By Alex Kershaw, author of The Bedford Boys, The Longest Winter, Avenue of Spies, The Liberator.

Flight Lieutenant Frank Howell, RAF 609 Squadron.

The mood was grim, both on the sand dunes where starving, exhausted Tommies waited for rescue, and in London, where even in Churchill’s War Cabinet there was talk of a compromise peace with Hitler. Churchill ended all such defeatist sentiment, telling his cabinet in an emotionally charged meeting on May 28: “I am convinced that every one of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long island story of ours is to come to an end at last, let it end only when each of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

Churchill’s defiance was met with cheers and hurrahs. It was clear that he now had every one of his cabinet firmly on his side. “Quite a number,” he recalled, “seemed to jump from the table and come running to my chair, shouting and patting me on the back . . . had I at this juncture faltered at all in leading the nation I should have been hurled out of office. I am sure that every Minister was ready to be killed quite soon, and have all his family and possessions destroyed, rather than give in.”

Just as the cabinet had rallied to Churchill, so would the nation. But first, something had to be salvaged from the disaster unfolding at Dunkirk. Senior commanders hoped that perhaps thirty thousand men, a fraction of the British Expeditionary Force, might be saved. In London, Ambassador Kennedy added his own assessment to the general air of doom, cabling President Roosevelt that: “Only a miracle can save the BEF from being wiped out or, as I said yesterday, surrender . . . the English people, while they suspect a terrible situation, really do not realize how bad it is. When they do I don’t know what group they will follow, the do or die or the group that wants a settlement.”

But all was not yet lost. The seafaring nation was beginning to respond to a call for all available vessels to make the hazardous Channel crossing and evacuate men from the bloodstained beaches. All manner of craft, from private dinghies to Thames tugboats, were headed toward Dunkirk. Above the beaches, Fighter Command’s Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons were also now in action, fighting with unprecedented aggression, many of their pilots furious at the sight of their countrymen being mowed down as they waded in long snaking lines toward rescue boats. Even veteran Luftwaffe pilots, who had readily strafed columns of refugees in Spain and destroyed Guernica, soon began to sicken of the slaughter. For twenty-four-year-old Captain Paul Temme, flying at three hundred feet above his victims, it was “just unadulterated killing. The beaches were jammed full of soldiers. I went up and down ‘hose-piping.’ It was cold-blooded point-blank murder.”

The fighting over Dunkirk would be a prelude to the Battle of Britain, and the Luftwaffe and the RAF took careful measure of each other. For the first time, the Germans encountered the full force of Fighter Command, and it was soon clear that the RAF’s Spitfires and Hurricanes were just as lethal as the Messerschmitt Me-109, the Germans’ best fighter. Another thing was quickly obvious: the British pilots were as well disciplined and courageous as their foe in the air, confirming the warning of influential First World War veteran Theo Osterkamp: “Now we fight ‘The Lords,’ and that is something else again. They are hard fighters and they are good fighters.”

For many RAF pilots, Dunkirk was a chaotic and brutal baptism of fire. “The Me-109s were quicksilver,” recalled one squadron leader. “It would have been ideal to come against them as a controlled formation, but the Germans always split up, so somehow you did, too. Then it was every man for himself—which was all right if you were good.” Thankfully, some were very good indeed. They included twenty-eight-year-old Flight Lieutenant Frank Howell of 609 West Riding Squadron, a strikingly handsome, blond-haired former mechanic who, on June 1, 1940, was appointed a flight leader after two days of fierce combat.

In a remarkable letter to his brother, Howell provided a vivid account of what it was like to fly above the hell of Dunkirk: “The place was still burning furiously, a great pall of smoke stretching 7,000 feet in the sky over Belgium . . Thousands and thousands of A/A [anti-aircraft] shells were bursting over the town . . . I looked down to see salvo after salvo of bombs bursting with terrific splashes in the water near some shipping, and there was a Heinkel, only 500 feet below going in the opposite direction so I did a half roll, and came up its arse, giving it a pretty 2 seconds fire . . . All the way back to England I flew full throttle at about 15 feet above the water and the shipping between England and Dunkirk was a sight worth seeing. Paddle boats, destroyers, sloops, tugs, fishing trawlers, river launches . . . anything with a motor towing anything without one . . . I am indeed lucky to have got away scot free. Dizzy was killed and five other chaps are missing. One was my flight commander so I am now in charge of A Flight, and will get another stripe, and it’s a rotten way to get it.”

On June 1, Winston Churchill was back in Paris, again trying to rally the French and sharing with them the heartening news that more than 165,000 troops had been pulled off the beaches at Dunkirk. Distressingly, his exhortations to fight on to the very end appeared to fall on deaf ears. Churchill’s escort from Paris back to England was to be provided by 601 Squadron, otherwise known as the Millionaires’ Squadron because several of its pilots came from wealthy families. “Winston was ebullient as ever,” recalled an aide. “When we started back he insisted on pacing round the aerodrome to review [601’s] nine Hurricanes, tramping through the tall grass in the flurry of propellers with his cigar like a pennant.”

British Major General Sir Edward Spears remembered “nine fighter planes drawn up in a wide semi-circle around the Prime Minister’s Flamingo . . . Churchill walked toward the machines, grinning, waving his stick, saying a word or two to each pilot as he went from one to the other, and, as I watched their faces light up and smile in answer to his, I thought they looked like the angels of my childhood. These men may have been naturally handsome, but that morning they were far more than that, creatures of an essence that was not of our world: their expressions of happy confidence as they got ready to ascend into their element, the sky, left me inspired, awed and earthbound.”

One of these angels, Flying Officer Gordon “Mouse” Cleaver, remembered that morning somewhat differently.13 The night before, the Millionaires had become rip-roaring drunk: “There assembled at Villacou-blay just about as hungover a crew of dirty, smelly, unshaven, unwashed fighter pilots as I doubt has ever been seen. Willie [Rhodes-Moorehouse] if I remember right was being sick behind his aeroplane, when the Great Man arrived and expressed a desire to meet the escort. We must have appeared vaguely human at least, as he seemed to accept our appearance without comment, and we took off for England.”14 By June 4, the evacuation of Dunkirk was officially over with an incredible 338,226 Allied troops removed from the beaches to England. Göring’s promise that “not a British soldier will escape” had been ludicrous. He had simply been “talking big again” as General Alfred Jodl, Chief of Hitler’s General Staff, was quick to point out.15 In a week of almost constant combat above Dunkirk, the RAF had shot down 132 German planes for a loss of 99 of its own fighters, 5 from Flight Leader Frank Howell’s 609 Squadron. It was a remarkable performance, or as Churchill described it to his War Cabinet, “a signal victory which gives cause for high hopes of our successes in the future.”

The British Expeditionary Force had been saved by some 693 boats of all sizes, many of them “little ships”—dinghies, pleasure yachts, skiffs, tugboats—a quarter of which were sunk. But now it had nothing to fight with. Almost all the BEF’s armor and weapons had been left behind, leaving England practically defenseless. The evacuation of Dunkirk could certainly not be described as a victory, but it was nevertheless a powerful tonic to both the British people and the rest of the free world.

The post Dunkirk From The Air appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post The Modified M3 Grease Gun in WWII appeared first on World War Media.

]]>

The .45 caliber submachine gun M3 is often indicated as being a success story of small arms design and development during World War II. Born of the necessities and exigencies of a full national wartime mobilization, it is best known for the economy of scale it provided and the modesty of its manufacturing costs.

by Martin K A Morgan

At peak production, M3s were a bargain at $20.94 each – that’s less than half the cost of the cheaper, mass-production version of the Thompson submachine gun. Although low cost was a major factor in the M3’s success, so too was the speed of its development and adoption. The project went from a concept on paper, to the T20 prototype, to adoption and production within just seven months, a record that no other firearm in U.S. military history has ever challenged. When it went into production in May 1943 at GM’s Guide Lamp Division plant in Anderson, Indiana, the M3 was a reliable open-bolt submachine gun weighing just over eight pounds with a fully loaded 30-round detachable box magazine. It’s design made extensive use of sheet metal stampings to include the two halves of the receiver assembly, the trigger, the rear sight, and a crank handle on the right side of the gun used to retract the bolt before firing. The M3’s sheet metal construction made it lighter and cheaper to produce, and gave it an appearance resembling an auto mechanics grease gun. But sheet stampings also created one weakness that would soon reveal itself on the battlefield.

A right side view of M3 submachine gun #0061260 – an early pattern Grease Gun produced at GM’s Guide Lamp Division plant in Anderson, Indiana in 1943. The red arrow shows the delicate bolt retracting “crank handle” that created the need for a field modification. (Photo courtesy of the National Firearms Museum)

On Tuesday, June 6, 1944, U.S. troops used the M3 Grease Gun in action for the first time. During the weeks that followed, it fought a vigorous campaign stretching from Normandy through to the liberation of Paris and the push to the Siegfried Line. Soldiers carried it up hill and down valley through the adversity of dust, rain and, eventually, even the snow. They were beat-up as the troops climbed on and off of trucks, half-tracks, and tanks. While an M3 could survive being dropped on its left side without affecting its ability to function, dropping one on its right side was another matter entirely because that is where the weapon’s fragile sheet metal retracting handle was mounted to the trigger housing assembly.

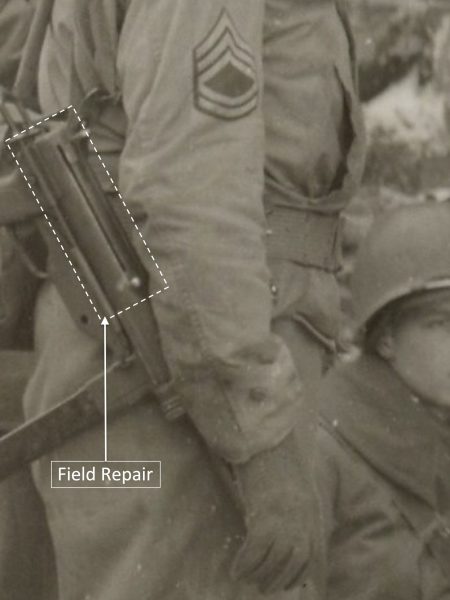

An officer in the headquarters of the 253rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion/6th Armored Division reads the “Articles of War” to his men on January 20, 1945 in the village of Mageret, Belgium three miles east of Bastogne. Note the Sergeant First Class at far left is armed with a field modified M3 submachine gun. (Official U.S. Army photograph)

On numerous occasions during the closing months of 1944, U.S. Army soldiers dropped M3 Grease Guns in such a way that they broke off crank handles. With no retracting mechanism, the bolt could not be drawn to the rear and, the weapon could not be used. At the time, the Army’s ordnance companies were ready to repair just about any infantry weapon in inventory, but not the brand new Grease Gun. In the rush to develop and the adopt the weapon, the potential for breakage of the inherently vulnerable crank handle was overlooked with the result that, when it finally began to happen in France after the D-Day, there was no prescribed method of repairing the problem and, more importantly, no spare parts. This meant that repairmen had to improvise and make due with what they had on hand.

A field modified M3 submachine gun in the collection of Musée National d’Histoire Militaire (the National Military History Museum) in Diekirch, Luxembourg. The weapon’s crank handle has been removed, a slot has been cut in the receiver and a makeshift cocking handle has been added to the bolt.

The solution was straightforward and simple: ordnance company personnel started by removing what was left of the retracting handle assembly from each damaged weapon, then used an end mill to cut a seven-inch long slot into the right hand side of the receiver at the 2 o’clock position running from just behind the weapon’s ejection port. This accommodated a crudely hewn steel bolt handle that inserted through an enlarged opening at the forward end of the slot and entered a hole drilled into the back end of the bolt assembly. It was not a pretty repair, but it worked. A few archival photographs of men from General George Patton’s Third Army taken around the time of the Battle of the Bulge show Grease Guns repaired in this manner. In addition to that, the collection of Musée National d’Histoire Militaire (the National Military History Museum) in Diekirch, Luxembourg has in its collection five M3s that have received this field modification. Considering the fact that the Third Army operated in Luxembourg during and after the Battle of the Bulge, it looks like this field modification may have been confined to the ranks of that specific unit. Interestingly enough though, a product improvement was already in development back in the USA that would make this design shortcoming superfluous.

A field modified M3 submachine gun in the collection of Musée National d’Histoire Militaire (the National Military History Museum) in Diekirch, Luxembourg. The weapon’s crank handle has been removed, a slot has been cut in the receiver and a makeshift cocking handle has been added to the bolt.

As early as April 1944, Guide Lamp was working on the modified M3E1 submachine gun. In addition to a number of other design refinements, it featured the complete elimination of the M3’s crank handle assembly and its replacement with a simplified, and indestructible, finger hole in the bolt. The substantial weight of the M3’s bolt was such that the pressure exerted by the weapon’s dual mainsprings was only eighteen-pounds. This meant that the old crank handle apparatus was not just unnecessarily complex, it was unnecessary altogether because the physical effort of retracting the bolt could be managed comfortably by the shooter’s index finger alone. No lever device necessary. On December 21, 1944, the M3E1 was officially adopted as the .45-caliber submachine gun, M3A1 – coincidentally at the same time that field modified M3s were fighting the German onslaught 4,000 miles away in the Ardennes Forrest. Although the fragile crank handle issue was fully resolved with the introduction of the M3A1, the crude and yet perfectly functional field modification that it produced nevertheless says something complimentary about ordnance technicians during World War II. When confronted with a significant repair job on a new weapon with no replacement parts available, they had to adapt, adjust and overcome, and they had to do it quickly. It is a testament to the skill and know-how of these Army gunsmiths that they came up with a practical solution under less than ideal circumstances.

A close-up view of M3 submachine gun #0061260 showing its bolt retracting “crank handle” and ejection port. (Photo courtesy of the National Firearms Museum)

The post The Modified M3 Grease Gun in WWII appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post In Silent Tribute appeared first on World War Media.

]]>IN SILENT TRIBUTE- Back in 2002 while writing Tonight We Die as Men (TWDAM) with Roger Day we described a plane crash on June 6, 1944, near a small isolated Norman farmhouse known as Les Rats situated one mile north of the wooden bridges at Brevands. The two bridges were the D-Day objectives of 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, who were the main subject matter of our now historic book.

By Ian Gardner- Author of Tonight we die as men, Deliver us from darkness, No victory in valhalla and Airborne: the combat story of Ed Shames

Time had dimmed the collective memories of our French and American veteran contributors but undaunted we persevered and eventually concluded that ‘our plane’ was probably a single-engine US fighter – possibly even a P-47 Thunderbolt. After we learned that a group of nomadic gypsies had cleared away the wreckage in the late 1940s we felt there was little point in any further investigation and besides it had no real synergy with our story at the bridges.

Following its release in 2009, TWDAM peaked the interest of British ex-pat Tony Graves, who after several visits to the long overgrown and now water-filled crater at Les Rats, gained permission from the French authorities and began a series of excavations that would span the next two years. The following summer Tony was shocked to discover that ‘our P-47’ was in fact a British Avro Lancaster, codenamed ND739Z belonging to 97 Squadron from the Royal Air Force. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) here in the UK still had the aircraft and crew listed as ‘missing’. It is also interesting to note that right from the outset the MOD were very much against Tony digging but were powerless to stop the exhumation of what they considered to be a potential war grave. However, by now Tony was on a mission to locate what might remain of the wreckage and with it hopefully the missing crew. It soon became apparent that ND739Z was no ordinary ‘Lanc’ nor was its pilot, Wing Commander Edward Carter and his seven crew members (one more than usual) who collectively were among the highest ranked and decorated in Bomber Command.

During the early morning hours of D-Day, 97 Squadron’s task was to bomb the German coastal artillery site at Pointe du Hoc. As lead aircraft, ND739Z was equipped with H2S, a highly specialised and secret ground scanning radar system, first introduced in 1943 (hence the need for an extra crewman). Ironically, unbeknown to the men or their RAF superiors, the guns at the Pointe had been moved to a nearby country lane overlooking Utah Beach and as such, the mission was already doomed to failure. Shortly before 5am, after successfully bombing the target, Carter and his squadron came under unexpected attack from a Focke Wolfe FW190, flown by Hauptmann Helmut Eberspächer. Leaving a trail of smoke and flames in their wake, Carter’s plane lit up the early morning skies off the Normandy coast before slamming vertically into the ground at Les Rats. Based near Tours and by pure chance Eberspächer just happened to be patrolling along the beaches when he spotted the Lancaster’s silhouetted above him. Within four minutes the German night fighter ace had brought down three British bombers including ND739Z.

In late September 2012 Tony Graves invited me to join him and his team for what was to be their last and final dig at Les Rats. From a depth of around 30 feet, two Merlin engines, several tons of wreckage and a number of personal items came to the surface but bizarrely the remains of the crew were nowhere to be found? This led Tony and myself to speculate that any human remains had probably been removed and reburied by the gypsies who salvaged much of the shallow surface debris for scrap after the war. Tony kindly allowed me to take a souvenir back to the UK – a shattered piece of engine block complete with bolts, split pins and inspection stamps.

On October 4, 2012, my local newspaper The Camberley News and Mail published an article about the dig. A few days later I received an emotionally charged phone call from James Chapple, the journalist who had covered my story. James told me to sit down and then said, “Ian, you won’t believe this but I have just spoken to Keith Dunning, whose father Guy, was the Flight Engineer on that plane!”

Unbelievably Pilot Officer Guy Dunning had lived in Camberley (three miles from where I live now) before the war where he had met his wife Lillias. By an amazing twist of fate, Keith who was 18 months old when his dad was posted as missing now resides in the nearby town of Yateley – literally just around the corner from my mother Joan! The next week after his article was published as a follow up to mine, Keith showed me all of his dad’s letters (including his last) and explained that the attack on Pointe du Hoc was Guy’s 54th operational sortie and that in the April he had not only qualified as a Pathfinder but had also been commissioned and awarded The Distinguished Flying Medal. Sadly Keith’s mum Lillias, had died a few years before the crash site was discovered, always believed that her husband’s aircraft had come down in the English Channel. Strangely she felt that Guy had survived and held on to this unshakable belief until the late 1950s when she finally accepted the fact that her husband was never coming home.

I donated my souvenir piece of engine wreckage to Keith and it now rests in his fireplace on a plinth in silent tribute to the father he never knew. This story is still unfinished and perhaps one day someone will stumble across the final resting place of Guy Dunning and his comrades – until then their names will remain on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede along with 20,276 other men and women who have no known grave.

The post In Silent Tribute appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post Shooting a Vickers Machine Gun at 240 frames per second appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The Vickers machine gun has what is perhaps the greatest reputation among recoil operated belt-fed water-cooled machine guns. Adopted by the U.K. in 1912, it proved itself in the crucible of World War I trench warfare a superlative of ruggedness and reliability.

By Martin K.A. Morgan

In one notable example from the Battle of the Somme, the 100th Machine Gun Company was assigned the task of delivering a 12-hour barrage of sustained fire against German trenches 2,000 yards away. Ten Vickers machine guns were put to the task, and they opened fire during the afternoon of August 23, 1916. When the guns ceased fire the next day, they had expended just under one million rounds of .303 ammunition.

Each Vickers had ripped through almost 100,000 rounds with only occasional interruptions to change barrels. The fact that each of these 10 guns could sustain such an incredibly high volume of fire clearly indicated the asthonishing engineering strength of the Vickers machine gun system – a system that would serve U.K. forces for over five decades. Only a small fraternity of military firearms enjoys unquestioned esteem and admiration the way that the Vickers does. It carved its name into the military history of the 20th Century through decades of reliable service, and it continues to reaffirm its prodigious reputation here in the 21st Century.

During a recent day of shooting in southern Louisiana a 100 year old Vickers that was made at the Crayford Works just east of London was put to work firing brand new .303 ammunition made in Serbia by Prvi Partizan. Although it was not asked to fire 100,000 rounds in 12 hours, it nevertheless turned-in a predictably flawless performance, the proof of which can be seen in this video.

The post Shooting a Vickers Machine Gun at 240 frames per second appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post The Escape Route of Joachim Peiper- Interactive appeared first on World War Media.

]]>“After daybreak cleared, Peiper pointed to a fir tree, sparkling brilliantly in the sun. “Major, he said with a sardonic smile, “the other night I promised you I would get you a tree for Christmas. There it is.”

By Ann Hamilton-Shields

I was hooked by those two sentences. The summer of 1984 flew by as I plowed through the Time/Life WWII series – but it was Peiper and the Battle of the Bulge that wouldn’t let me go. Who were these soldiers escaping through a snowy forest on Christmas day, 800 Germans with a lone American hostage? Thus began a 32 year fascination with Kampfgruppe Peiper’s 1944 breakout from La Gleize.

Skipping forward to 2004, I was a civilian nurse for the US Army living in Germany with my family. We had visited La Gleize a time or two and Peiper’s breakout pulled at me every time. But where to start? Out of the blue a friend sent me Major General Micheal Reynold’s article “Escape from the Cauldron”, prompting an avalanche of reading on the Bulge and more specifically, Jochen Peiper.

Over the years my amateur study of WWII blossomed. We attended veteran affairs, trekked through battlefields, toured museums, and became acquainted with the dedicated network of WWII experts in the European Theater.

Meeting author Danny Parker at a 2007 museum opening in Baugnez kicked off a new phase in my interest. We chatted: “So, you’re writing a bio of Peiper? He’s my favorite German bad boy – a paradox of good and evil.” The conversation flowed and a week later I was one of Danny’s many manuscript readers.

My role soon expanded into scouting and photographing locations from Peiper’s life. In Berlin, chasing Peiper’s history was not difficult: a flat in his Ruedesheimer Platz building, the building next door to his bombed-out childhood home, his elementary school, the Wansee yacht club (where I snuck in with help from the kitchen staff), his wedding and reception site, an apartment in the building where “Little Bunny” Potthast lived, and of course the Lichterfelde Barracks complex. The cooperation of the Berliners was astonishing.

In 2008, my husband and I arrived at the La Gleize museum after a day tracking Kampfgruppe Peiper’s route. Mr Gregoire walked me outside and pointed to the rocky trail where Peiper and his men slipped out of town. Twentyfour years had passed since I first read about MAJ McCown and Peiper – now it was time to put on the hiking boots.

Danny Parker’s meticulous research provided the backbone for my numerous hikes. The lack of specific directions was frustrating until I realized the Germans themselves didn’t know exactly where they had walked during that grueling 36 hours. My early hikes (2009-2011) were solo endeavors as I scouted out each segment with a sweaty conglomeration of maps and documents, struggling to meet my worried husband at a pre-arranged time and place. I fought brambles, insects, blisters, mud – and the staff at Wanne chateau, where I was asked to leave!

In 2011 my worry about descending the steep face of Mt St Vincent alone was solved when I met Doug Mitchell. This ex-pat US Marine had what I didn’t: a military sense of tactics and terrain, excellent photographic skills, and fluent German. Add an affable spirit with well-used hiking boots and we were a pair. Tracking Peiper’s trail in its entirety was happening!

During the summer of 2012 Doug and I walked the breakout using our combined sources. I won’t go into the wrong turns and painful backtracks involved – and must mention that in true USMC fashion Doug didn’t complain! Major General Michael Reynolds graciously reviewed our work, including over 200 photographs, and pronounced it a match with the eyewitness reports he’d collected in the 1970’s from German vets.

Over the course of our research, many WWII history friends had expressed interest in walking the route of Peiper’s breakout. This idea became a reality in October 2012 as our hardy group left La Gleize on a fall morning, arriving in Wanne about eight and a half hours later. It was a fourteen mile day of ascents and descents, sun and rain, and “aha!” moments when sites recorded almost seventy years ago popped into view. There was no snow, no hunger, and no machine gun fire….just history under our boots, and the satisfaction of nailing down a mystery before it was too late.

The post The Escape Route of Joachim Peiper- Interactive appeared first on World War Media.

]]>The post Operation Stösser: Kampfgruppe Von der Heydte in the Ardennes (Part II) appeared first on World War Media.

]]>In picturesque Monschau– famous for its slate-roofed half-timbered houses– exhausted Fallschirmjäger desiring to surrender to U.S. forces sought out towns people. Better to give up to fellow Germans than risk being shot when surrendering to the enemy. This gained new import with rumors from the Latrinenparole that SS men– Kampgruppe Peiper– had murdered surrendering Americans just south of where they had landed. Between 21 and 24 December, over a hundred Fallschirmjäger gave themselves up to civilians in the town. “Sometimes we went out to take the paratroopers into custody,” remembered Paul Henze with its military government, “but usually we told the tactical troops of the MPs where the paratroopers were located and they went to pick them up. Nearly all were suffering from exposure and trench foot.”

by Danny S Parker author of FATAL CROSSROADS & HITLERS WARRIOR www.dannysparker.com

Also read Operation Stösser: Kampfgruppe Von der Heydte in the Ardennes (Part I)

The American military government officials knew nothing of the extent of the parachute operation– many estimating it to contain several thousand men that might suddenly rise up confront the unwary. The military government had made its headquarters in the Hotel Horchem– the finest of the twelve hotels in the town, disproportionately endowed as Monschau was a famous destination for honeymooners. Captain Robert A. Goetscheus, the head of the military government and a lawyer from Indianapolis, could not be too sure that his otherwise complacent citizens might suddenly revert to their previous sympathies.

The relationship of the 2,600 natives of Monschau to the early occupation had been uneasy since the Americans had taken over in September. Food, medical supplies and clothing had been short all autumn and many citizens were bored, unable to freely come and go and limited by curfews. Several locals made the observation that the Nazi government had never been this oppressive. However, the worst had come in October when, the members of Combat Command B of the 5th Armored Division– whose commander was wildly anti-German– had suddenly forcibly evacuated all the residents of nearby Kalterherberg and proceeded to loot the town. Even in Monschau there was a huge problem with thievery, GIs making off with furniture, radios, stoves and even cars. Then too, the non-fraternization policy was a total failure and by November, every willing German woman in Monschau had been seduced.

For weeks, the U.S. V Corps worried that sympathizers in the town were feeding information to the Germans, but the local government did not dwell of that certainty– as it was, enemy forces– known to include the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division– were on the sharp ridge line that looked right down into the town’s narrow cobble-stone streets. They could see everything and sometimes would even send artillery cascading into the town. Indeed a 15-man German patrol came into the town on 1 October and threatened the Burgomeister at pistol point at his own home for cooperating with the Americans.

The danger of living with the enemy so close became clear to the American occupational forces on Saturday, 16 December. That morning Monschau and the towns on either side, became the northernmost objective for Dietrich’s 6. Panzer Armee assault charged to the LXVII Armeekorps. In the German plan, the Vorausabteilung– the single partly-motorized detachment of the 326. Volksgrenadier Division built around 4 assault guns and the fusilier company was to strike through Monschau and push along the Eupen road to possibly help link up with Kampfgruppe von der Heydte. The northern talon of the German assault would unhinge the American forces defending in the Elsenborn area. Hitler himself had personally called for a super-heavy Jagdtiger Battalion (s. Panzerjäger Abteilung 653) to be participate in the advance on Eüpen, but delayed by the air power-pulverized German rail system to the rear, the single available company of 80 ton monsters had not arrived on the eve of the offensive. Still, very heavy artillery support was assigned: 405.Volksartillerie Korps and the 17. Volkswerfer Brigade turned tubes to the west for a massive barrage to help blast the infantry companies forward.

However, word had it that Genfldm. Model, himself had expressly forbidden artillery fire on Monschau, the fairy-tale resort and a favorite destination for honeymooners. Thus, the town largely escaped the pounding barrage that hit both the sectors to the north and south at 5:30 AM. One of the few shells to fall into Monschau a dawn struck right outside the Hotel Horchem spraying the dining room of the U.S. headquarters with shrapnel and sending everyone leaping under tables.

Thirty minutes later, a surprise attempt by the 326. Volksgrenadier Division to rush into Monschau along the winding Rohren road– materialized when the German infantry attempted to cross the road block on Rosenthalstrasse. Alerted by the shelling, troopers of F Company, 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron fired lethal canister from M5 Stuart light tanks at close range. The brazen German infantry pulled back with heavy losses. A second attempt, to enter the town at 8:30 AM from the “snake road” leading from Imgenbroich to the north and nearby wooded draws was also punished by American artillery, with the columns retreating in disarray. Meantime, unsophisticated human-wave assaults south of the town against the 3rd Battalion of the 99th Infantry in Höfen were similarly destroyed. These offensive jabs were so costly to Genmaj. Erwin Kaschner’s grenadiers– 20% casualties– that the division would make no further real contribution to Wacht Am Rhein. The Volksgrenadier mission to link up with Kampfgruppe von der Heydte never got started.

Back in the German village of Monschau, everyone was shaken. Over the succeeding nights, “artificial moonlight” eerily lit up the Monschau skyline. The illumination came from lines of searchlights on the German side, intended to help nighttime infantry assaults move forward. Enemy artillery barrages fell to the north and south upon nearby Mützenich hill and Höfen. Meanwhile, scores of German aircraft passed directly overhead on the night of December 17th while strong infantry assaults eddied back and forth against Höfen and Mützenich. The German assault followed on each of the following two days. These incursions were only turned back by the U.S. forces with great difficulty and the mood in town was somber.

With electricity out, on the night of 18 December, Capt. Goetcheus and his staff, has supper inside the Hotel Horchem under the light of Hitler Jugend torches that had been discovered in the basement. They were under pressure from V Corps to evacuate the town, but managed to resist this notion at least partly due to the certainty that Monschau like Kalterherberg would have been roundly pillaged. “One shooting; two looting,” went the joke. 9th Infantry Division, now arriving in town, had shown that tendency.

Von der Heydte wounded-captive

Still, with reports of a large-scale German parachute operation in the vicinity, by 20 December, the nervous tension in Monschau reached a fever pitch for both panicked civilians and the military government alike. Elaborate searches began of the woods and swamps between the town, Eupen and Malmédy. The operation to flush out von der Heydte’s men in hiding consumed the 18th Regiment of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division and a Combat Command B of the 3th Armored Division. “American soldiers were seeing German paratroopers behind every bush.” In Monschau itself a fruitless house-to-house search began on the night of the 21st. Even if none were immediately found, that disappointment was not to last.

Then in the late afternoon, the three men awoke to plod down toward Monschau crossing the Rur River. But now, reaching the edge of the village and finding no friendly forces– American soldiers only– von der Heydte stopped in disappointment. Barely able to walk, he couldn’t continue. He insisted the other men go on without him around Monschau and seek German lines. He would just hold them up. Only with his direct orders, did they leave their Colonel hiding in the brush. Shivering in wait until dark that Thursday evening of 21 December, von der Heydte finally got to his feet and staggered ahead into town. At 11 PM, the Baron pushed the doorbell of one of the first house he came to in Monschau. It was a squat two story structure with a slate-covered dormer roof at Monschau at Am Oberer Kalk 6 just west of the main road.

Hearing the doorbell, 56-year old schoolteacher, Karl Bouschery found an ailing German officer outside the lattice work door. The man was shivering and hurt; Bouschery led the man inside, supporting one shoulder. Baron Von der Heydte promptly collapsed in the warm kitchen to the wooden floor. The family gathered around him by the glowing wood stove. Bouschery had himself been in the trenches in World War I and although everyone in Monschau had watched the tanks surge triumphantly through the town in 1940, four years later he was disparaged the war and the NSDAP. When the family was able to speak to Von der Heydte, he seemed to feel the same way. “I’m sick and too weak to fight,” he said. He was on the verge of pneumonia. “In the morning I will surrender.” The Baron drank the ersatz coffee made from wheat berries the family fed him, but was too sick to eat any food. Eugene was trained in first aid and splinted von der Heydte’s broken fingers with tongue depressors.